Member of Behrend’s first class had high-flying career as a NASA test pilot.

It took only three months working the night shift at a steel forging plant in Pittsburgh in 1947 for Don Mallick to decide to go to college.

“It was an extremely tough job, often leaving me with burns on my hands and arms,” he said. “Soon, I realized my parents had the right idea about college.”

A new Penn State campus—Behrend Center—had just opened, and Mallick was one of the first 150 students in the inaugural class. He majored in Mechanical Engineering and spent a year at Behrend before transferring to University Park, as all students had to do in the early days of the college.

“When I got there (University Park), I found that the other students referred to Behrend students as coming from ‘the country club,’” he said. “Behrend really did have a beautiful setting, but it was a place of serious study.”

Mallick did not end up finishing his degree at Penn State, though. He wanted to fly planes like his older brother, and the Korean War gave him a reason to interrupt his college education. At 19, he was too young to fly for the U.S. AirForce but old enough to fly for the U.S. Navy. By 1952, hehad earned his wings.

He served as a Navy fighter pilot on three different aircraft carriers in the European and Pacific theaters.

Back to school

Once his four-year commitment was up, and with a wife and growing family, Mallick decided to return to college at the University of Florida in the aeronautical engineering department. He kept flying as an active Navy Reserve member.

“Once a month, I could blow the cobwebs of study out ofmy head by flying the F9F-6 Cougar jet in the reserves,”he said.

Shortly after graduation, he landed a job as a test pilot at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which would eventually become part of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

“When I was offered the job, I earned a salary of $7,700 a year, which was nearly $1,000 less than a job I had been offered in the private sector, but money was not my primary consideration,” Mallick said. “I just wanted to fly.”

At the forefront of modern aviation

NACA/NASA favored military officers as test pilots because they had experience, nerves of steel, and a willingness to face dangerous situations. It’s risky work. Test pilots are the first to take unproven technology into the sky to see how it works.

“I tested new fighters, helicopters, multi-engine aircraft, small amphibian aircraft, and some vertical takeoff and landing machines,” Mallick said. “After one year of flying at NASA, I had the confidence to fly almost anything.”

The testing done at NASA’s Langley facility in Virginia, where Mallick worked at the time, primarily involved improving aircraft stability and handling qualities. Mallick conducted three notable programs there:

The F-86D wing shaker program. “At times, the conditions resulted in so much aircraft motion, you couldn’t read the instrument panel,” Mallick said.

The F8U-3 Sonic Boom Program, NASA’s first program to document the nature and strength of sonic booms that reached the ground. It was Mallick’s introduction to flying in a pressure suit. “Runs were made to 60,000 feet and at Mach 2.0,” he said.

A ground-based confinement simulation of the trip to the moon. For this, Mallick and two other NASA research pilots spent up to a week at a time in a space capsule set up in a large, darkened room. Complex memory tests were conducted during the simulation, and the pilots had to perform maneuvers on an active flight panel. The information gained was vital to future moon missions.

A move to California

In 1963, Mallick; his wife, Audrey; and their four children moved to California, where Mallick began work at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center. There, he reached the pinnacle of his career, even flying rocket-powered aircraft.

“Over the years at Dryden, I participated in dozens of programs, including the Blackbird Program, which involved ten years of testing the aircraft’s propulsion, structure, heating, stability, control, and more,” he said.

In 1967, he was promoted to chief pilot at Dryden, assigning and monitoring pilot programs and overseeing pilot safety.

“I didn’t lose one pilot in seventeen years as chief, and I consider this one of my greatest achievements,” he said.

When he retired as deputy chief of Dryden’s Aircraft Operations Division in 1987, Mallick had accumulated more than 11,000 hours of flight time in 125 different aircraft.

Mallick’s odyssey

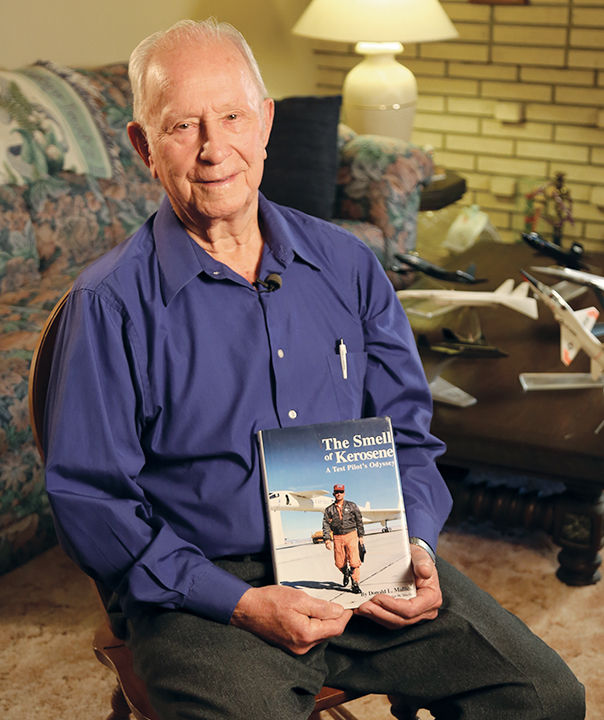

After retiring, Mallick wrote two books–a family history book and a book about his flying career. “The Smell of Kerosene: A Test Pilot’s Odyssey” was published by NASA in 2004.

“I was pleased and proud they published it,” Mallick said. “I think it was the first one that NASA published for one of their pilots.”

A one-hour documentary based on the book was recently finished, and the producer hopes to find a buyer for it soon.

Today, at 92, Mallick is still living independently in California.

“During my career, I saw both triumph and tragedy,” he said. “Research and test flying is a hazardous profession. I had good friends who were killed flying. I have great hopes there is a world after, and that one day, I will share a drink and some good stories with them again.”