Alumna forms nonprofit to mentor, inspire youth of color

Jacqueline Jackson ’02 can’t remember a time she wasn’t mentoring someone.

“It’s important because it holds me to a higher standard,” Jackson said. “Knowing there are people who look to me as an example encourages me to push harder.”

As a student at Behrend, Jackson, who earned concurrent degrees in Marketing and International Business, served in several leadership roles. She was a resident assistant, president of the Association of Black Collegians, on student government and on the Multi-Cultural Council, among other activities.

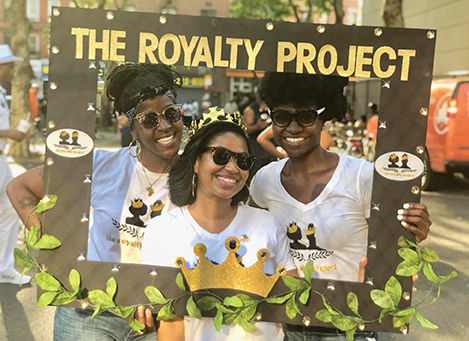

When she graduated and began her career in corporate retail, she continued reaching back to help others achieve as well. She has a special interest in empowering young people, which is why, three years ago, she formed a nonprofit organization, the Royalty Project, a cultural enrichment initiative in Harlem, New York, serving youth of color ages 10 to 14.

“Mentoring kids is the fountain of youth,” Jackson said. “Children are fearless, unbiased, and natural risk takers. They are a huge inspiration to the adults who embrace and engage with them. Mentoring is truly rejuvenating.”

Labor of Love

The Royalty Project is a side venture for Jackson, who has spent the past seventeen years working for retail brands such as The Gap, Ralph Lauren, Coach, and Kate Spade. This year, she pivoted from fashion to home décor, joining West Elm in New York City as director of inventory planning for decorative accessories.

She formed the Royalty Project with friends, many of whom serve on the board of directors for the organization.

“We had been casually discussing ways to contribute to our community and culture for some time and came up with the idea of a mentor program,” she said. “We developed the idea, branded the concept, solicited community partners, and organized a launch party in less than a year. Fortunately, it was well received and successful even though I was impetuous. We made some rookie mistakes that took years to correct.”

Among those mistakes was getting a web address with a dot-com domain instead of a dot-org address—and launching before The Royalty Project, was officially recognized as a 501(c)(3).

“All is well now though,” she said. “Mistakes were corrected, and lessons were learned.”

Such is life and business—a series of lessons learned the hard way. In any case, who could fault Jackson

About the Royalty Project

“The name was chosen to convey ‘ascension,’” Jackson said. “The painful history of African-Americans has produced a large amount of self-doubt in our community. Considering ourselves royalty conveys that we are called to a higher standard.”

The Royalty Project is an eight-week program offered twice a year, in the spring and fall. Students participate in Saturday workshops that include activities and discussions about the history and culture of African descendants. They also go on a group field trip before the class culminates with a graduation ceremony, dubbed “The Crowning.” Both women and men serve as mentors for the Royalty Project.

“Everything we do is co-facilitated by a male and female team,” Jackson said. “We partner to prepare for and lead the activity together. It’s a great way to exhibit cooperation between genders.”

It’s an important, if subtle, life lesson. It’s just one of many that Jackson and her volunteers hope to convey.

“Self-awareness leading to self-esteem grounded in the substance of legacy is the special sauce,” Jackson said. “We work to share and embody the beauty that comes from a painful past by telling our own history. So often, our history and culture are depicted and narrated by people or groups who aren’t a part of it. It’s important that we narrate our own stories.”