Imagine you are an artist who creates flying machines—large installation pieces that bring lobbies and public spaces to life. Picture big, kinetic sculptures made from copper, brass, and glass with motorized parts that whir, move, and catch light on geometric slices of glass, mesmerizing all who pass by. Now, think back to the 1970s, before the internet and cell phones when artists had to sell their work in person. How would you fit a 14-foot installation piece on an airplane to New York City or San Francisco?

Perhaps you would build a miniature replica. Something that encapsulated the essence of your work but would still fit under the airplane seat in front of you.

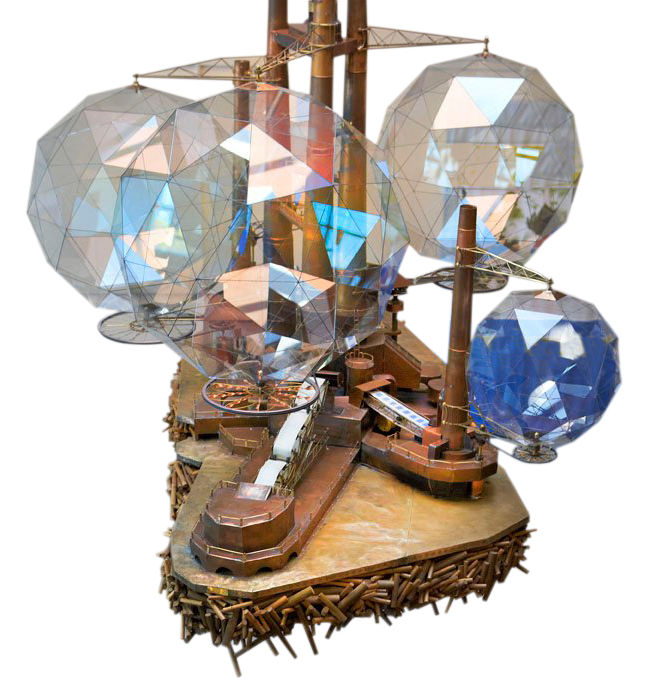

That’s why Erie artists David Seitzinger and John Vahanian created Joe the Box, a miniature (7 inch by 7 inch by 14 inch) version of their large installation pieces, like the Lighter than Air Paper Factory sculpture commissioned by the former Hammermill Paper Company (founded by the Behrend family) that now hangs in Burke Center.

“Photographs just don’t tell the story of our work,” Seitzinger said in a 1978 public television interview posted on YouTube. “You really have to see it in action.”

However, lugging an enormous piece of fragile artwork was not only impractical but impossible.

“We needed something we could pick up with two hands and set down and operate,” Vahanian said. “Something small that would hopefully convince people they should commission a larger piece.”

So, the artists created Joe the Box, a model and working piece of art that was, in the artists’ words, fickle.

“It comes up and does something different every time,” Vahanian quipped in the television interview.

Fifty years later, Joe the Box, which had been purchased by a Vahanian family member, wasn’t coming up at all. They tried to have it repaired and asked Vahanian to fix it. He no longer had the tools or equipment to do so, but he reasoned the School of Engineering at Penn State Behrend might.

In October of 2022, he reached out to Dean Lewis, assistant teaching professor of mechanical engineering, to see if Joe the Box might be a potential senior design project.

While the sculpture didn’t fit the parameters for a senior design project, Lewis had another idea: Given the complicated motorization mechanisms, maybe the Behrend Robotics Club could restore it.

“A few robotics club members and I met with Mr. Lewis to see and learn more about it,” said Adam Sacherich, a Mechanical Engineering senior. “We decided as a club that it would be an exciting project to work on.”

Engineering News talked with Sacherich to learn more.

How would you describe the Joe the Box art piece?

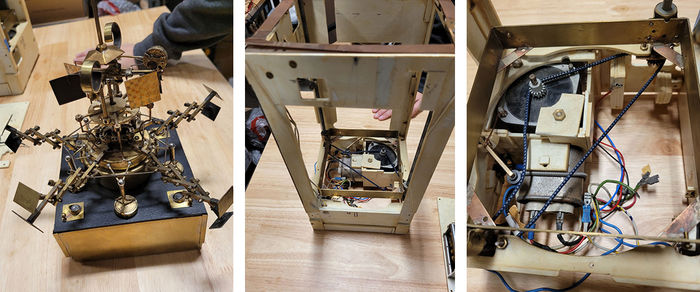

From the outside, it looks like a simple brass box. However, once a button near the base of the box is pressed, the top of the box opens, and a spinning glass globe raises from the inside. As the globe spins, multiple arms extend and retract while moving up and down. Once the globe spins for about a minute, it returns to the brass box and the lid closes behind it.

What was wrong with the piece?

The glass globe would not rise, and the top of the brass box wouldn’t slide open. Additionally, the wires were unplugged and mislabeled from a previous attempt to fix the piece.

What interested the Robotics Club in taking on this project?

The club was intrigued for a few reasons:

Its mechanical nature perfectly aligned with the club’s interests.

The parts originally used on this project were old and custom-made. This meant replacement parts could not be easily sourced. Instead, the club would have to design a way to use new parts on this project. This was an interesting challenge.

We were fascinated by the simplicity of the electronics in the piece. Even though it has complicated timing requirements to prevent all the parts from colliding, there’s not a single computer chip. Instead, a washing machine timing box controls the motion. We wanted to fix the piece while maintaining its unique control system.

What was the club’s challenge?

We needed to design a new mechanism for raising the globe, design a new system to open the top of the box, and figure out where all the wires needed to be plugged into. All of this needed to be done without changing the piece’s appearance or adding any modern control electronics.

How did members troubleshoot the project?

It was a lot of trial and error. We would 3D print a replacement part, test fit it, redesign it, and then repeat the process until we created functional parts.

How long did it take to fix Joe the Box?

The project turned out to be more complex than it initially appeared, so it took about three semesters to figure it out. We accepted the project in October of 2022 and completed it in December of 2023.

When it was finally operational, what were the club members’ reactions?

We were all very happy. It had taken more time and effort than we anticipated, but seeing it finally run without issue made it all worthwhile. Everyone liked the piece, so we were happy to restore it. All the club members helped, but students heavily involved included myself, David Konkol, Alan Everett, Adam Robertson, and Ben Hollerman.