Jump to any section below.

Appendix A: Selected Data on NTL Promotions

Supporting data tables:

Table 1: NTL Promotion Averages and Range.

Source: Annual University Faculty Affairs NTL Promotion Flow Reports

|

Year |

# |

Avg |

Range |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2018-19 |

75 |

7.0% |

4-8% |

|

2019-20 |

67 |

7.0% |

4-8% |

|

2020-21 |

44 |

7.2% |

3-8% |

|

2021-22 |

58 |

7.0% |

4-8% |

Table 2: NTL Promotion Raise Estimates Across the Commonwealth

| Distribution |

# Promoted |

Fraction |

Raise |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Behrend |

19 |

10.2% |

4% |

|

Other 3% |

2 |

1.1% |

3% |

|

Other 4% (estimate) |

22 |

11.8% |

4% |

|

Other 8% (estimate) |

143 |

76.9% |

8% |

|

Total |

186 |

7.06% |

| Distribution |

# Promoted |

Fraction |

Raise |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Behrend |

19 |

10.2% |

4% |

|

Other 3% |

2 |

1.1% |

3% |

|

Other 6% (estimate) |

45 |

24.2% |

6% |

|

Other 8% (estimate) |

120 |

64.5% |

8% |

|

Total |

186 |

7.05% |

Further commentary on the recommended change:

The obvious repercussion of such a change is that GSI for all faculty will decrease. However, that is a perspective that does not take into account the full picture. Under the current policy, TT promotions are 8%, funded directly by UP. Then, GSI is used to provide 4% promotion to NTL faculty, and the remainder of GSI is distributed among NTL and TT faculty. The result is that long-term TT faculty members’ raises will pull significantly ahead of otherwise equivalent NTL peers receiving the same number of promotions.

Quantitatively, based on the average number of NTL’s receiving a promotion each year at Behrend for the 2018 to 2020 academic years, the decrease in the GSI received by all faculty in order to fund NTL promotions at 8% instead of 4% would be less than $8 / $10k of salary. For example, if GSI for a particular year is 2%, then a faculty member with a salary of $100k would receive a GSI raise of $1,840 instead of $1,920 in order to ensure equitable treatment of NTL and TT faculty.

Finally, concern has been raised regarding what should be done in the future if past events such as no GSI (as in 2020) or centrally allocated uniform 2% GSI (as in 2022) are repeated, since in such events there is no new unallocated money in the budget. First, we believe it is the responsibility of the leadership to figure out how to make the budget work in a way that is equitable to Behrend’s employees. In such an event, it is recommended that, if at all possible, the promotions be funded by shifting money within the existing budget. If such is necessary and permissible, these funds could potentially be replaced using the following year’s GSI, as that should have been the initial source of the funds in the first place. In the absolute worst-case scenario of full promotion raises being impossible, it would be best to simply give as much as possible immediately, with the remainder to be made up the following year.

Appendix B: Summary of School-level Data on Workload and Evaluation Methods

The Committee agreed that we will survey representatives from each school for this charge, primarily requesting information related to the Annual Review and workload policies. The complete responses to these survey requests are available upon request and summarized here.

Tenured and Tenure Track (TT) Teaching Loads:

The base teaching load of 18 credits per academic year (AY) appears to be consistent across schools. However, adjustments to the base load are school specific. Business offers a reduced teaching load of 15 credits to support research, administrative, and other service assignments, and junior faculty on the TT. Business also has a policy under which tenured faculty will receive increased teaching loads for falling short of continued research expectations. Engineering incorporates a point system to adjust for labs and supervision of senior design projects. Science offers course releases for TT faculty and faculty in “high-demand” service positions. Also consistent across schools are the job description weights for teaching (45%), research/scholarship (45%), and service (10%).

Non-tenure Line (NTL) Faculty Workload policy:

The base teaching load of 24 credits per academic year (AY) appears to be consistent across schools. However, adjustments to the base load are school specific. Business offers a course release to support a “significant level” of research, if resources permit. Engineering incorporates a point system to adjust for labs and supervision of senior design projects. Science offers course releases for NTL faculty in “high-demand” service positions. Also consistent across schools are the job description weights for teaching (60%), research/scholarship (30%), and service (10%), except for H&SS, which reports teaching (52.5%), research/scholarship (30%), and service (17.5%).

Average Class Sizes for 100 and 200-level courses:

-

Business is unreported. Business only offers a small number of 100 and 200-level courses (ECON 102/104, ACCTG 211, and MIS 204/250).

-

Engineering is 8-25 students, depending upon department.

-

Science is 60-90 students. Science has a large number of 100 and 200-level courses.

-

H&SS is unreported.

Average Class Sizes for 300 and 400-level courses:

-

Business is 30-35 students.

-

Engineering is 12-35 students, depending upon department.

-

Science is 20-50 students.

-

H&SS is unreported.

Annual evaluations are conducted by (a committee, a supervisor, someone else).

The annual evaluation process also differs between schools. In Business, annual evaluations are conducted by department chairs based upon completed AFAR reports. Evaluations in Engineering are conducted by the leadership team of department chair (primary evaluation), other chairs (review only), and school Director (review). Evaluations in Science are conducted by a committee of elected faculty representatives and the school Director. H&SS evaluations are conducted by the school Director.

Annual evaluation is quantified with point values and weightings (or is it subjective or some other high-level structure).

Business and H&SS conduct annual evaluations using a weighted point system, while Engineering employs a weighted system based upon qualitative measures. Science uses an elected Academic Personnel Review Committee who assigns numerical scores for teaching, scholarship, and service that are based upon qualitative measures (e.g., excellent, very good, satisfactory, etc.). The committee reports these scores to department chairs and the school Director, who meet and assign final scores for each faculty member.

What is the research expectation for TT faculty? Is it quantified and specific?

Business relies on the research points from the AFAR reports to assign ranges for qualitative measures (i.e., excellent, very good, satisfactory, and unsatisfactory). Engineering uses a subjective approach based upon lists of “primary criteria” and “secondary criteria” that are specified in the school’s policy handbook. Science and H&SS report ”…no specific research expectations…” and “It is not clearly stated…”, respectively.

What is the research expectation for NTL faculty? Is it quantified and specific?

Each school has the same process for evaluating NTL faculty as they use for TT faculty. However, for each school, TT faculty have higher expectations in both quality of targets and quantity.

How is the service expectation measured?

Because service incorporates a wide variety of activities, it is broadly measured in each school. However, each school appears to strongly consider the impact of service activities in their evaluation.

What is the value for the faculty member in being “excellent” versus “very good”?

Engineering reports that faculty earning consistent ‘excellent’ ratings are more likely to be promoted. However, none of the other schools reported a value.

Appendix C: Committee Actions Regarding BCF 10

The subcommittee reviewed BCF 10 as charged (through Faculty Senate) by Dr. Silver in academic year 2021-2022. The work was not completed last academic year, so it was carried over to academic year 2022-223. The current subcommittee recommended revisions to the document and shared these revisions in an email from Luciana Aronne to Dr. Silver on Feb 6, 2023. Dr. Silver replied on the same day that she would share the suggestions with Dr. Ford. In an email on Feb 16, 2023, Dr. Silver declined to meet with Luciana because the Chair of Behrend Faculty Senate (Dr. Lisa Jo Elliott) deemed Charge #3 “unconstitutional”, and the work done by the subcommittee “invalid”. The committee thought that the charges had been approved in total in the fall semester, but there was disagreement on this issue. This matter was resolved when Faculty Council officially approved the charges on April 3, 2023, at the request of Eric Robbins (chair of Faculty Affairs).

On April 4, Eric Robbins (chair of Faculty Affairs) informed the Faculty Affairs committee that charges may continue. On the same day Luciana and Lena Surzhko Harned (vice-chair of Behrend Senate and member of Faculty Affairs) met and discussed dates for Town Halls open to all faculty to discuss the suggested revisions to BCF 10 (Charge #3).

On April 12, 2023, Dr. Ford called a meeting with Lisa Jo, Lena, and Eric to discuss Charge #3. Dr. Ford felt that this charge deserved a more comprehensive review, so we are recommending, in fall 2023, that Faculty Senate should hold two listening sessions led by Luciana Aronne who will still be a member of Faculty Affairs. These listening sessions should only be composed of faculty. The intention is to gather concerns that faculty have with BCF 10. After the listening sessions, we recommend that the Faculty Senate Chair should then charge an ad hoc committee comprised of members of both administration and faculty to discuss ways to adequately address these concerns. We recommend that the committee should be comprised of NTL faculty from across the schools who have utilized BCF 10 at their school and college promotion committees because they provide the unique insight and institutional memory needed to revise BCF 10 so that it is a clear, fair, and accessible document. It is recommended that Sharon Gallagher and Luciana Aronne serve as part of the faculty contingent given the work they have already done on these revisions this past academic year.

Appendix D: Faculty Affairs Survey Spring 2023

Respondents

The Faculty Affairs survey was sent to all Behrend faculty on Wednesday, April 5, 2023, and it closed on Friday, April 14, 2023. During that time, 83 individuals completed the survey. Forty-four of those individuals were tenure-track faculty and 39 were non-tenure-track faculty.

Frequencies of tenure and non-tenure track faculty completing the survey by school is displayed in Table 1. Of those completing the survey, nine individuals have worked at Penn State Behrend for less than 5 years, twenty-four have worked at Behrend between 5 and 10 years, and fifty have worked at Behrend for more than 10 years.

Table 1: Summary of Survey Demographics

|

School |

Tenure-Track |

Non-Tenure Track |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Business |

8 |

9 |

17 |

|

Engineering |

9 |

5 |

14 |

|

Humanities and Social Sciences |

12 |

10 |

22 |

|

Science |

13 |

14 |

27 |

|

Other |

2 |

1 |

3 |

GSI

For the 2021-2022 academic year, the university provided a non-merit-based GSI. We understand that this was a decision that was passed down by University Park and not independently imposed by Behrend’s administration. In order to gather opinions regarding the non-merit-based GSI from the 2021-2022 academic year, individuals hired after July 1, 2021, were excluded from the analysis. Seventy-six faculty members responded to questions regarding the non-merit-based GSI. Of those responding, 9 (13.64%) felt the non-merit-based GSI was a positive motivator, 39 (59.1%) felt the GSI had no impact on their motivation, and 18 (27.3%) found the non-merit GSI to be a demotivator. More specific information on motivation to perform in major areas of work is shown in Table 2 and Table 3. In sum, 31.7% (N = 20) prefer the non-merit-based GSI and 68.3% (N = 43) prefer the merit-based GSI from years prior to the 2021-2022 academic year.

Table 2: Faculty Perception of Motivation in Response to Non-Merit Based GSI By Evaluation Area

| Evaluation Area |

Do More |

Do the Same Level |

Do Less |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Service |

10.6% (7) |

65.2% (43) |

24.2% (16) |

|

Research |

11.1% (7) |

71.4% (45) |

20.6% (13) |

|

Teaching |

15.6% (10) |

75.0% (48) |

9.4% (6) |

Table 3: Faculty Perception of Motivation in Response to Non-Merit Based GSI By School

|

School |

Motivates |

Does NOT Motivate |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Business (N = 14) |

42.9% (6) |

57.1% (8) |

|

|

Engineering (N = 10) |

60.0% (6) |

40.0% (4) |

|

|

Humanities & Social Sciences (N = 15) |

46.7% (7) |

53.3% (8) |

|

|

Science (N = 21) |

52.4% (11) |

47.6% (10) |

|

Annual Review Process

Regarding the Annual Review process, which differs across schools, faculty reported different opinions in their schools’ process. Table 4 shows the approximate time spent on the annual review. Twelve individuals found their annual review to be objective, while 17 felt like the annual review process was subjective. Others (N = 37) reported their process as being a mix between objective and subjective and five were unsure how to rate their annual review process. Approximately 49.2% (N = 30) respondents reported feeling motivated to achieve excellence by their annual review process, while 50.8% (N = 31) feel the review process does not motivate them to achieve excellence.

Table 4: Time Spent on Annual Review Preparation

|

Time |

Frequency |

|---|---|

|

<1 |

1 |

|

1 -2 hours |

10 |

|

2 - 3 hours |

18 |

|

3 - 4 hours |

13 |

|

4 - 5 hours |

14 |

|

> 5 hours |

16 |

An examination by school was conducted and displayed in Table 5 below.

Table 5: Faculty Perceptions on the Objective vs. Subjective Nature of Their School’s Review Process

|

School |

Objective |

Subjective |

Mix |

Unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Business (N = 16) |

56.3% (9) |

0 |

43.8% (3) |

0 |

|

Engineering (N = 11) |

18.2% (2) |

36.4% (4) |

45.5% (5) |

0 |

|

Humanities & Social Sciences (N = 19) |

0 |

31.6% (6) |

57.9% (11) |

10.5% (2) |

|

Science (N = 24) |

4.2% (1) |

25% (6) |

58.3% (14) |

12.5% (3) |

Workload

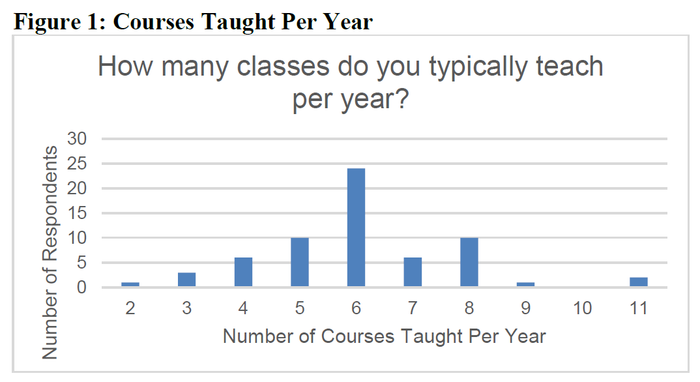

Respondents were asked a series of questions regarding the typical number of courses taught per academic year, the number of contact hours per course, and the typical class size. Figure 1 shows the typical number of courses taught per year (N = 63). Of the typical courses taught per year, 30.8% (N = 20) respondents said their contact hours with students was equal to the credit hours per course, 66.2% (N = 43) reported more contact hours than credit hours for their typical courses, and 3.0% (N = 2) reported less.

Respondents reported an average enrollment of 48 students in their courses, with the majority (N = 38) having between 30 and 40 students in their typical course. Of the 63 respondents, 65.1% (N = 41) felt their teaching workload was appropriate and 34.9% (N = 22) felt their teaching workload was too high. Table 6 shows the reported impact of the teaching workload on areas of instruction, research, and service.

Table 5: Faculty Perceptions on the Impact of Workload

| Area | Negatively impacts % (N) |

No impact % (N) |

Positively impacts % (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Plan Instruction |

29.2% (19) |

63.1% (41) |

7.7% (5) |

|

Teach |

20.0% (13) |

67.7% (44) |

12.3% (8) |

|

Assess Learning |

40.0% (26) |

49.2% (32) |

10.8% (7) |

|

Engage in Scholarly Activity |

67.7% (44) |

26.2 (17) |

6.2% (4) |

|

Engage in Service |

40.0% (26) |

53.8% (35) |

6.2% (4) |

Potential Topics Needing Future Consideration

There were several responses to our open-ended question asking about future subjects that may require review by Faculty Affairs and/or Faculty Senate. Several are paraphrased and itemized below for consideration.

-

How are leadership positions assigned and rotated within the schools to ensure that all faculty have the opportunity for key service positions needed for promotion and tenure?

-

How are the various schools encouraging seasoned or tenured faculty to continue to be key contributors and not retire on the job?

-

The advising function at Behrend needs to be reviewed. Faculty advising vs. professional advising. Evaluation of advising as a part of faculty expectations.

-

Hold faculty listening sessions regarding AC 76 to assess faculty concerns.

-

Consider options for workload flexibility for NTL faculty since they teach far more sections (i.e., student hours) than TT faculty.

-

Options to enhance faculty’s sense of community to address the burn out that many are feeling right now.

-

Consider compensation disparity between the schools.

-

As student baseline performance has declined, post-COVID, faculty teaching effort has increased meaningfully. How can this be addressed more efficiently, equitably, and with higher outcomes for both students and faculty?

-

Is there a better way to reward and incentivize faculty to strive for excellence beyond their already engaged intrinsic motivations?

-

Teaching loads should reflect the number of students taught per section, not just the number of sections.

-

Is there an option for NTL faculty to shift their basis of evaluation from research to teaching/advising?

-

How can the University make faculty feel more validated for the outstanding work that they are already doing?

-

How could NTL faculty access sabbaticals to obtain much-needed breaks?

-

Are there tangible consequences for faculty who do not perform their duties as expected?

-

Concerns about the new University budget model's emphasis on student credit hours as the primary determinant for budgeting decisions. Report to Behrend faculty on what to expect by reviewing the impact this approach to budgeting other institutions.