A NASA-led team of astronomers has discovered five new planets, two of which are a habitable distance from their star.

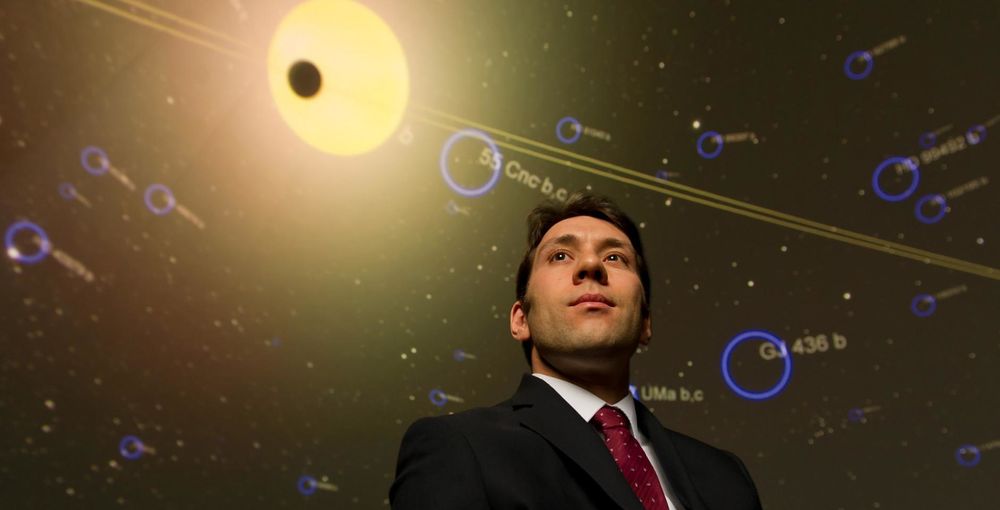

“It’s the system that most resembles the Earth’s,” said Justin R. Crepp, assistant professor of physics at the University of Notre Dame and a 2003 alumnus of Penn State Erie, The Behrend College. “These are the smallest planets we have found so far in a habitable zone.”

Size is a key factor in determining a planet’s potential for sustaining life. A planet two or three times the size of Earth is almost certain to be rocky, Crepp said. Larger planets are a mixture of rock and gas, or mostly gas.

A planet is within a system’s “habitable zone” when it is solid, with the possibility of water on its surface.

One of the new planets is 1.41 times larger than the earth’s radii, according to the new study, which was published in Science magazine. The other is 1.61 times larger than earth.

The planets were detected by astronomers using the Kepler space telescope. Kepler’s lens is focused on the Cygnus and Lyra constellations; it watches for variations in brightness in more than 100,000 stars.

A star’s intensity dims when a planet passes in front of it, casting a shadow. It’s difficult to see – NASA compares it to the brightness of a car headlight when a fruit fly passes by – but if the dimming repeats at regular intervals, astronomers have good reason to believe a planet is orbiting the star.

The star in this particular study is called Kepler-62. It’s roughly 1,000 light years from Earth.

One of the new planets transits, or passes in front of, Kepler-62 every 5.7 days. Others transit every 122 and 266 days.

Crepp studied the K-62 system from the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, eliminating any other factors – a binary star, for example – that could mimic the signatures of planets in transit.

The Kepler team has found planets before: 115 have been confirmed since the satellite launched in 2009. Most are far larger than Earth, and are made entirely of ice or gas.

Smaller planets are more difficult to see. But astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics now believe that 6 percent of red dwarf stars – the most common in our galaxy – have habitable, Earth-sized planets. Any one of them could fundamentally upend our view of the universe.

“Fifty years ago, you couldn’t imagine that this would ever happen,” Crepp said. “They are literally rewriting the textbooks as we speak.”