Matt Levy, an associate professor of art history at Penn State Behrend, has adopted an "ungrading" approach in several of his courses.

ERIE, Pa. — Good students tend to view their grades as the best measure of academic success. In college, however, that laser-focus on GPA can actually impede learning. Risk-averse students may be less likely to take chances or try out new ideas or ways of thinking, which is where true discovery and knowledge take shape.

To address that potential learning gap, several faculty members at Penn State Behrend have been experimenting with “ungrading,” an umbrella term for alternative assessment based on grading for growth. While methods vary, the concept of ungrading is based on providing feedback without judging too soon, before students have achieved the desired competency.

“Conventional grading methods tend to reduce students and their work to a snapshot of the process,” said Qi Dunsworth, director of the Center for Teaching Initiatives at Behrend. She hosted a “Grading Differently” open house for faculty members this spring.

“Ungrading practices motivate students to own their learning process by shifting their attention away from a definitive number or letter grade,” she said.

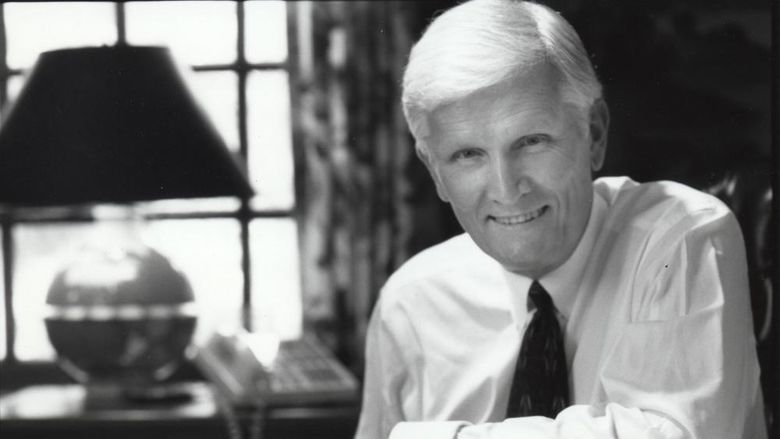

To learn more about alternative grading methods, we talked with three Behrend faculty members who have used the approach. Gabe Kramer, assistant teaching professor of mathematics, applied it in teaching Calculus I and II. Matt Levy, associate professor of art history, used it in three of his classes. Ashley Russell, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, used alternative grading in two of her molecular and cellular biology courses.

Why did you try grading differently?

Kramer: I was unhappy with having students’ first attempts at a skill being permanent in the grade book. I wanted to allow them to make mistakes and learn from them with minimal negative consequences.

Russell: In 2020, I implemented a “journal club” assignment in which I asked students to read original research articles that pertained to the material and summarize them. Students liked the assignment but were stressed about trying to include all the “right” information. It felt unfair to expect them to accurately summarize everything when some of it was so foreign to them. I wanted to keep these assignments but focus more on the reading and learning.

How did you apply these alternative grading methods?

Levy: I did away with high-stakes exams and replaced them with frequent, low-stakes pass/fail assignments. My new assignments prioritized personal reflection and application of class concepts over memorization and content recitation. I gave students more opportunities to learn from their mistakes, allowing them to retake quizzes and revise papers.

Russell: I utilized specifications grading for the journal club assignments. Each section of the summary was graded based on the specification, ‘Did you hit all the key points or make a valiant effort to?’ and it was graded pass/fail. For each section that they passed, they got one point. I added the points and multiplied them by a factor, and that was their grade for the assignment.

What were the results?

Kramer: Student feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. This type of grading allows for freedom in ways that traditional grading doesn’t. You can ask rich or complicated questions without fearing they are too difficult for students to answer, and students can attempt to answer them without fear of a ‘bad’ grade.

Levy: Because students were less worried about accumulating points, they took more intellectual risks and produced more personal and reflective writing. Students reported experiencing less stress and feeling they were learning for their own gratification, not just to earn a grade.

What else should people know about ungrading?

Kramer: It isn’t just unlimited do-overs. It’s a philosophy that embraces mistake-making as part of the learning process, and it gives students autonomy to learn at a pace more suited to them.

Levy: Some might assume it will result in a decrease in rigor or increased grade inflation, but my grade distribution is relatively unchanged from when I used a more conventional grading system.

Russell: It’s not a wishy-washy thing that lets students off easy. I still expect a lot from my students, and they know it. The pass/fail aspect actually seemed to light a fire under them to get it done.

Heather Cass

Publications and design coordinator

Penn State Erie, The Behrend College