Engineers are problem solvers by nature. So it should come as no surprise that when faced with a recycling conundrum, students in Penn State Behrend’s School of Engineering saw an opportunity.

The quandary

China, which is the largest consumer of recycled material from the United States, has significantly reduced the amount and types of material it will accept and introduced heavy restrictions on contamination, which is trash mixed in with recyclables.

This has forced a wave of changes in the U.S. recycling industry.

The bottom line: Recycling is becoming harder and more expensive for consumers and businesses to do and less profitable for material recovery facilities

It's not hard to see how this could lead to a breakdown in the recycling system.

Seeds of change

Recycling and the waste generated by landscaping containers is what led Valerie Zivkovich, a senior from Gibsonia, Pennsylvania, to the Plastics Engineering Technology (PLET) program at Penn State Behrend.

“I worked at a vegetable farm in high school, and we were constantly throwing out plastic containers that the plants were in,” Zivkovich said. “We couldn’t reuse them because of potential contaminants in the soil, and I understood that, but I thought there had to be a better way. I wanted to develop a better plastic for agricultural use.”

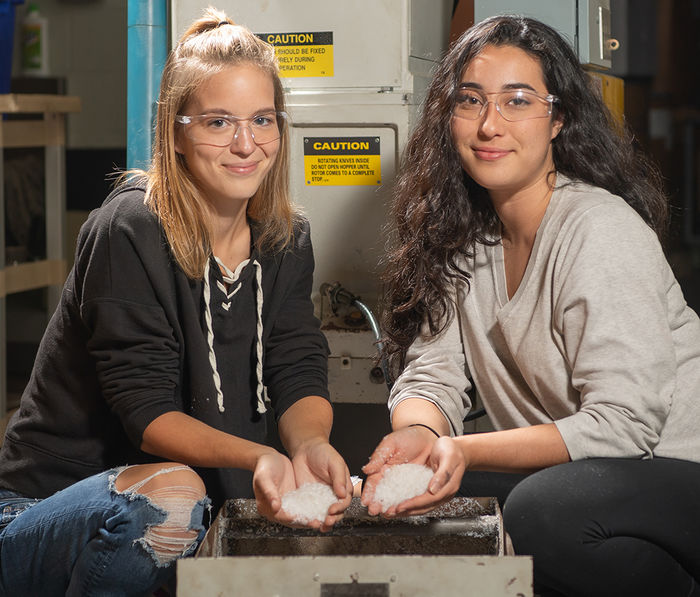

Zivkovich and her capstone project partner, fellow PLET senior Olivia Dubin, had heard the uproar from the Penn State Behrend community about the prospect of no longer recycling and began to think that the college could recycle its own plastic bottles.

At a campus-wide meeting with Waste Management officials, Zivkovich and Dubin presented a proposal to collect, clean, and pelletize bottles into raw material that could then be used to create new products.

“Basically, the process will involve collecting plastic bottles—primarily PET (polyethylene terephthalate) and PP (polypropylene) such as pop bottles, Starbucks cups, etc.—then grinding them up into tiny pellets and using or reselling them to a vendor,” Zivkovich said.

They worked on their initial plan with Jason Williams, assistant teaching professor of engineering.

“I think this could work because we already have most of the equipment and skills in our plastics department,” Williams said. “We are unique in that we have both a plastics factory and a research facility. This combination of resources makes Behrend a great place to test something like this.”

Waste Management agreed and awarded the students a $3,000 Think Green grant to help get the program going.

Williams is excited about the possibilities.

“I think this initiative is a valuable teaching tool and a demonstration of how engineers can make things better,” he said. “It will also give us tools we can use to study ways to handle post-consumer waste. I think there is a lot of research opportunity in developing automatic sorting technology and material handling of plastics.”

“As PLET majors, we learn about the impact and importance of recycling,” Dubin said. “We are excited to have come up with a solution that our whole campus could be involved in.”

It takes a village

The first step, Zivkovich said, is spreading the word about what can and can’t be recycled and the importance of rinsing containers before tossing them into the recycling bin.

“There definitely needs to be a campus-wide education campaign to teach others how to recycle properly— with information sessions, posters, and clear signage on the collection containers,” Zivkovich said.

Other priorities include finding more funding and securing workspace. “There’s a need for a new grinder and that’s $45,000,” Zivkovich said. “We’re applying for grants to find that funding. As for lab space, the Merwin building in Knowledge Park would be ideal.”

Another important part of the equation: volunteers from all four schools.

“Whatever major you are in, you’ll deal with recycling somewhere—at home, at work, in your community,” Zivkovich said. “This affects all of us, whether you work in the industry or not.”