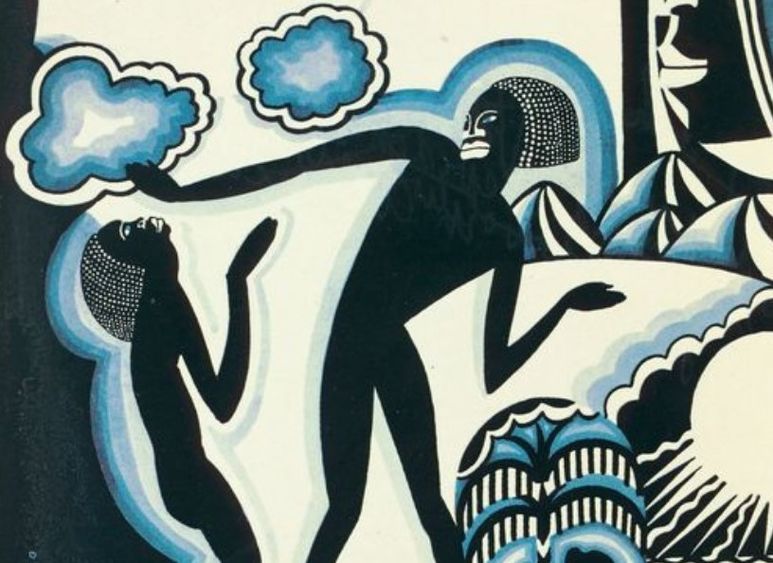

This illustration by Winold Reiss appears in "The New Negro: An Interpretation." A team of students at Penn State Behrend has updated the 1925 anthology, using digital tools to showcase the writing in new ways.

ERIE, Pa. — Alain Locke’s “The New Negro: An Interpretation,” an anthology of the Harlem Renaissance, was both a time capsule and a crystal ball: The book, published in 1925, included writing by Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay and Countee Cullen. Their voices, buoyed by a bold new sense of Black identity, would expand the literary canon.

“They were part of an artistic renaissance,” said Elisa Beshero-Bondar, a professor of digital humanities at Penn State Behrend, “and they were claiming their space.”

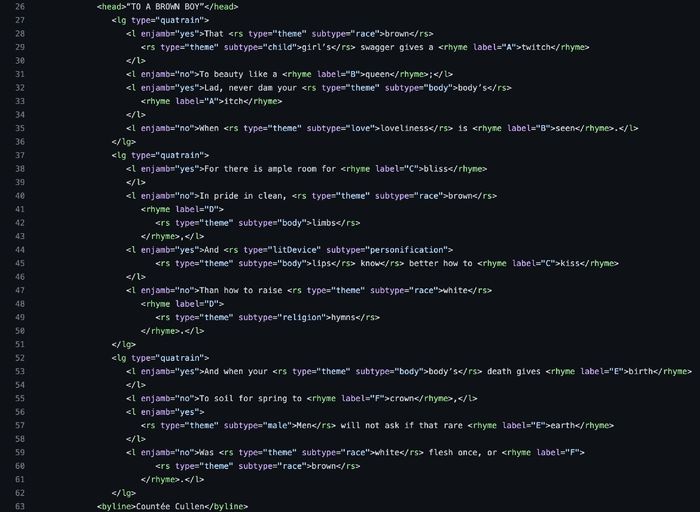

A team of Behrend students, working with a group at Framingham State University in Massachusetts, has developed a new way to read “The New Negro.” Using guidelines established by the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI), including formatting for machine-readable text, the students digitally encoded the anthology’s 37 poems. With color tags, word boxes, and background shading, they created a visual way of modeling the structure and theme of each poem.

“They broke the poems into pieces and applied these visual tags,” Beshero-Bondar said. “Now, when you read the poems, the colors jump out, signaling different aspects of the writing, from rhyme scheme and repetition to the use of metaphor.”

A team at Framingham State determined which words or literary devices would be highlighted. The Behrend students, using TEI, simplified the code, developing an ontology — a digital rulebook, essentially — that determined how the tags would be categorized. They also created a website, making the encoded poems — some of them highlighted with color-coded tags, and others enhanced with behind-the-scenes structural markups — accessible to the public.

Reading a tagged poem is like finding a highlighted passage in a borrowed book, said Bartholomew Brinkman, an associate professor of English at Framingham State. The marks reveal the architecture of a poem, but they also can impose the previous reader’s sense of the text.

“There is a bit of subjectivity to this,” said Brinkman, who first worked with Beshero-Bondar through the Digital Ethnic Futures Consortium. “If a student marks a passage, noting something thematic that we have been talking about in class, that’s a way of pinpointing a literary technique. It makes it concrete. That doesn’t mean it’s the only way to read the poem, however.”

Members of the team presented their work at the Keystone Digital Humanities Conference at Johns Hopkins University in June. They will discuss the project at the MEC/TEI conference in Paderborn, Germany, in September.

Brinkman hopes to continue the Behrend collaboration, adding features to the website that allow readers to select or clear certain categories of tags.

“One of the great things about a project like this is that it can live as it is and be useful to anyone reading the material today,” he said. “But we also can revisit it. We can expand it, adding features and giving readers more options.”

As they finished encoding the poems, the Behrend team turned to another feature in “The New Negro”: snippets of sheet music that appear between selections of traditional text. By using the Music Encoding Initiative (MEI), an open-source system for machine-readable music, the students converted the sheet music to MP3 files, which can be played on a computer.

“That was sort of a passion project,” said Zachary Dominick, a rising senior in the Digital Media, Arts and Technology program. “We had to manually put in a lot of data — every note, and the chords and accents and all that — but to press ‘play,’ and to hear a song from 1914 … that was awesome.”

The ability to hear that music, which fueled so much of the Harlem Renaissance, opens a new path through Locke’s anthology.

“It enhances everything else that is in there,” Beshero-Bondar said. “That’s what you live for in the digital humanities — the opportunity to take something static and breathe a new kind of life into it.”

Robb Frederick

Director of Strategic Communications, Penn State Behrend