Two Penn State Behrend faculty members will be featured in an online screening and panel discussion about “Hemingway,” the new PBS film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, on June 17.

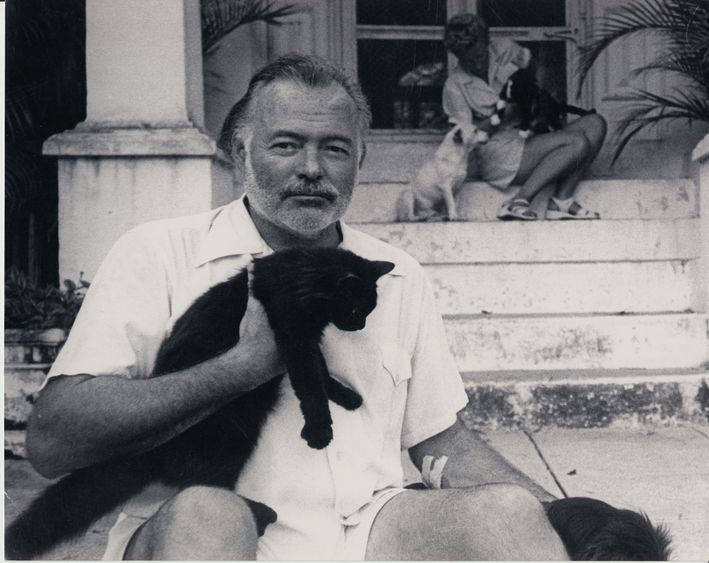

ERIE, Pa. — Two Penn State Behrend faculty members will be featured in an online screening and panel discussion about “Hemingway,” the new PBS film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, on June 17. They will explore Ernest Hemingway’s literary influence, which gave shape to the “Lost Generation,” and the larger-than-life public persona that trapped the writer in a caricature of empty-bottle masculinity.

The program will be livestreamed by WQLN Media, beginning at 7 p.m. To register, visit wqln.org/hemingway.

“Hemingway,” a three-part documentary, is both a celebration of the author’s writing, which earned Hemingway the Nobel Prize, and a reassessment of his turbulent public life, which ended in suicide in 1961.

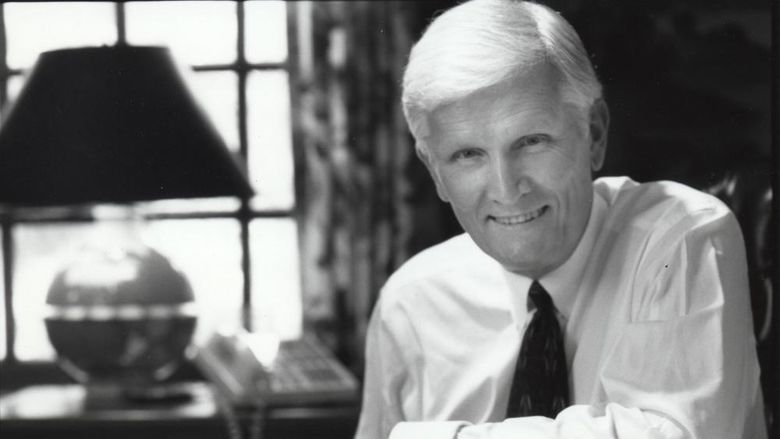

“Hemingway is still seen as having this defining gendered voice,” said Janet Neigh, associate professor of English and chair of the English program at Behrend. She will participate in the panel discussion, as will Tom Noyes, a professor of creative writing and English and chair of the creative writing program.

“The masculinity in Hemingway’s writing and his life became his brand,” Neigh said, “but his influence in the modernist movement, when authors were reinventing the possibilities of literature, also is significant. Hemingway, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot and others were breaking from the literary traditions of the 19th century, but they also were trying to process and represent what they saw as a very real crisis of meaning.”

For Hemingway, that centered on his experience in Italy during World War I, when he drove an ambulance for the American Red Cross. He was injured by a mortar blast, and again by machine-gun fire. His six-month convalescence in a Milan hospital inspired his 1929 novel, “A Farewell to Arms.”

“The trauma of World War I in many ways left people speechless,” Neigh said. “The language of the time lost much of its meaning. Hemingway responded to that by paring down his language. He streamlined it, and he developed a voice with more energy and immediacy than we had seen in the previous tradition, which was built on flowing, almost endless, descriptive sentences.”

Hemingway structured his writing like an iceberg: He believed the deeper meaning of a story should be implicit and kept just out of view. He relied on dialogue to drive the narrative forward, particularly in his short stories, trusting the reader to intuit the underlining themes.

“He perfected that economic style — spare, declarative sentences that suggested something heftier underneath,” Noyes said.

Hemingway’s lean, deceptively simple voice created a new genre, which led to Raymond Chandler, James Salter and Cormac McCarthy. That tradition continues: The June 17 panel discussion will include the winners of a WQLN-sponsored Hemingway writing contest. Noyes judged the fiction entries. Neigh judged the poems.

Reading the entries, Noyes found himself drawn again to Hemingway’s short stories. His favorites are collected in “In Our Time,” which was published a year before “The Sun Also Rises.” Eight of the stories feature the character Nick Adams as he faces various rites of passage.

“Hemingway was still honing his style,” Noyes said. “He wasn’t ‘Hemingway’ yet. There’s fishing and boxing and horse racing, but there’s also insight into how men’s lives are diminished if they reject femininity and are unable or unwilling to negotiate the gender divide.”

The stories that followed tested men on the battlefront, at the bullfights and far out on the ocean, alone, as they fought to bring in a fish as big as the boat. Those narratives distilled Hemingway’s vision of manhood. Off the page, however, they became a trap, typecasting Hemingway as a hard-drinking, lion-shooting, wife-betraying, macho Papa.

“Because of the themes in his writing, readers supposed they knew the kind of person Hemingway was,” Noyes said. “He saw opportunity in that, and he decided to wear it as a costume. Over time, it became a brand, and eventually, it became the man he was.”

Robb Frederick

Director of Strategic Communications, Penn State Behrend